Few names resonate through history with the power and mystique of Babylon. This ancient city, nestled in the heart of Mesopotamia, was more than just bricks and mortar; it was a crucible of civilization, a center of power, innovation, and cultural brilliance that left an enduring mark on the course of human history.

Our journey through time begins not with Babylon itself, but with the very land that nurtured its rise – Mesopotamia, the “land between the rivers.”

Before Babylon: Setting the Stage for an Empire’s Rise

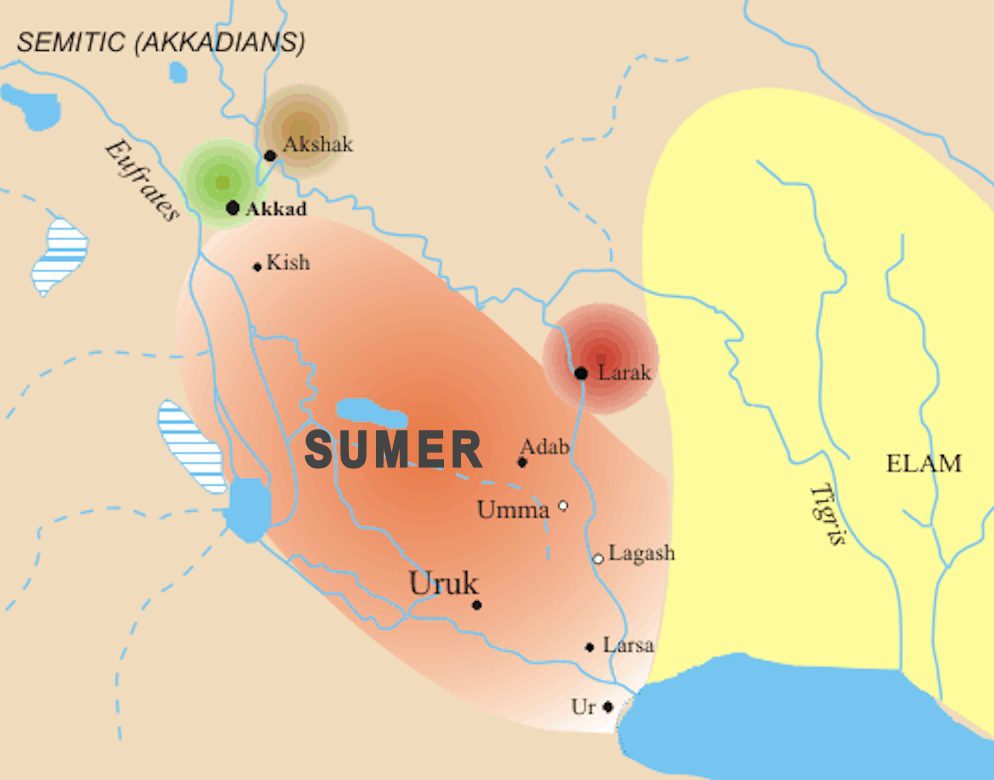

Imagine a world before empires, where humans lived in scattered tribes, reliant on the land’s bounty. In Mesopotamia, nestled between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, this nomadic life began to transform. This “Fertile Crescent,” stretching across modern-day Iraq, Kuwait, and parts of Syria and Turkey, possessed a unique geography that allowed for the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to settled agricultural communities. The rivers, prone to flooding, deposited rich silt onto the land, making it ideal for farming.

Around 3500 BC, this fertile ground gave rise to the Sumerians, often hailed as the “inventors of civilization.” From their city-states like Ur, Uruk, and Eridu, they developed groundbreaking innovations:

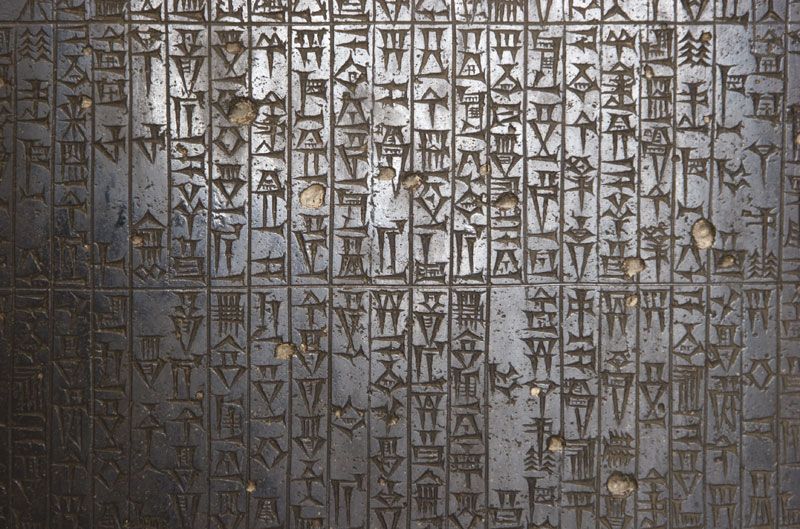

- Cuneiform Writing: Imagine pressing a wedge-shaped stylus into wet clay, creating symbols that could record thoughts, stories, and even complex laws. This was cuneiform, the world’s first known writing system, birthed by the Sumerians.

- Mathematics and Astronomy: The Sumerians were keen observers of the sky. They developed sophisticated mathematical systems, including a base-60 system that still influences our timekeeping (60 seconds in a minute, 60 minutes in an hour). Their astronomical observations laid the groundwork for later Babylonian advancements in this field.

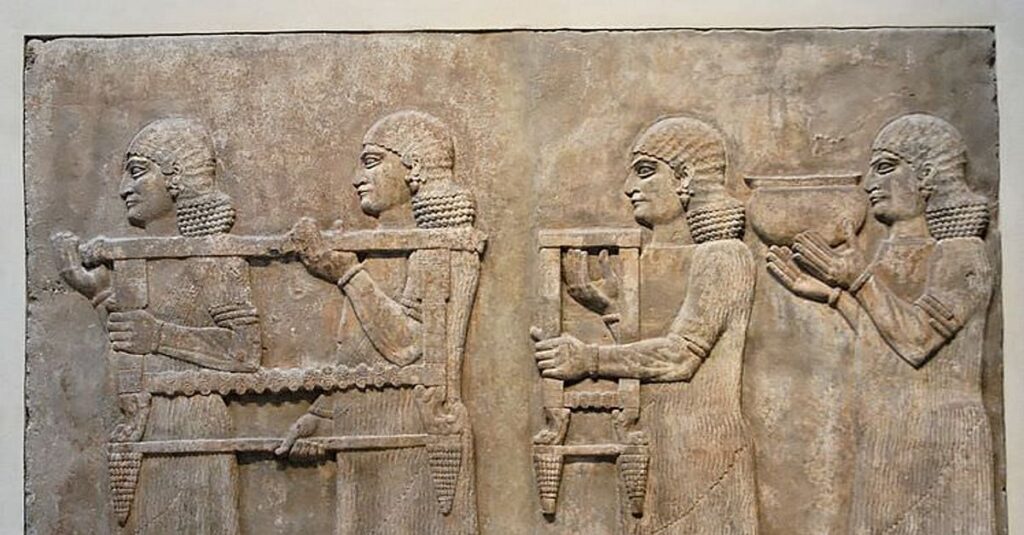

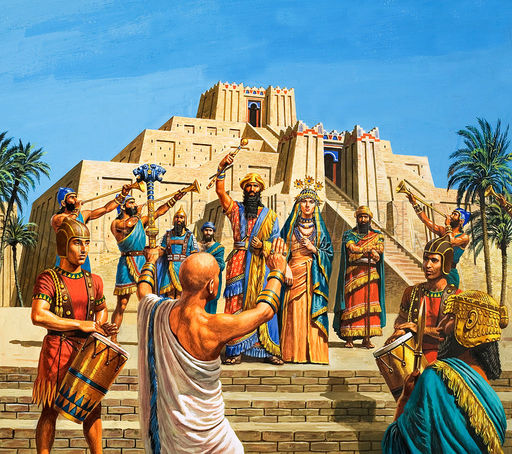

- Monumental Architecture: Ziggurats, massive stepped pyramids dedicated to their gods, dotted the Sumerian landscape, demonstrating their architectural skills and religious fervor.

However, the Sumerian city-states, often at odds with one another, proved vulnerable to conquest. This set the stage for the rise of Sargon the Great of Akkad, who, around 2300 BC, unified these city-states and forged the world’s first empire – the Akkadian Empire. Sargon’s empire, though relatively short-lived, established a precedent for large-scale political unification in Mesopotamia, paving the way for future empires, including Babylon, to emerge.

By the 21st century BC, a new force entered the Mesopotamian stage: the Amorites, a Semitic people migrating from the west. Amidst the political fragmentation that followed the collapse of the Akkadian Empire, the Amorites established themselves throughout Mesopotamia, with one particular city on the Euphrates River becoming their crown jewel: Babylon.

The First Babylonian Dynasty: A Star Rises on the Euphrates

While the Amorites were establishing themselves in Babylon, the city was by no means destined for greatness. It was but one of many competing city-states vying for power in a volatile region. It was the ambition of one man, Sumu-abum, that would change Babylon’s destiny forever.

In 1894 BC, Sumu-abum declared independence from the weakened rulers of the time, establishing the First Babylonian Dynasty. This marked the birth of the Babylonian Empire. However, his successors would face a constant struggle to maintain their grip on power. Early Babylonian rulers were adept at playing the political game of ancient Mesopotamia. They engaged in:

- Strategic Alliances: Marriages between royal families cemented alliances and expanded Babylonian influence.

- Military Campaigns: When diplomacy failed, the Babylonians were fierce warriors, expanding their territory through strategic conquests.

- Administrative Reforms: To govern their growing territory effectively, these early rulers established systems of taxation, law enforcement, and infrastructure development.

King Sin-Muballit (1812-1793 BC) stands out for significantly expanding Babylonian territory and strengthening the city’s defenses, laying the groundwork for his grandson, Hammurabi, to usher in a golden age.

Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC): The Legacy of Law and Order

Few names are as synonymous with ancient Babylon as Hammurabi. Ascending the throne in 1792 BC, he proved to be a brilliant military strategist, a shrewd diplomat, and a visionary lawgiver.

Hammurabi’s reign saw Babylon rise to become the dominant power in Mesopotamia. Through a series of carefully orchestrated military campaigns, he subdued rival city-states, expanding his empire’s reach from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea.

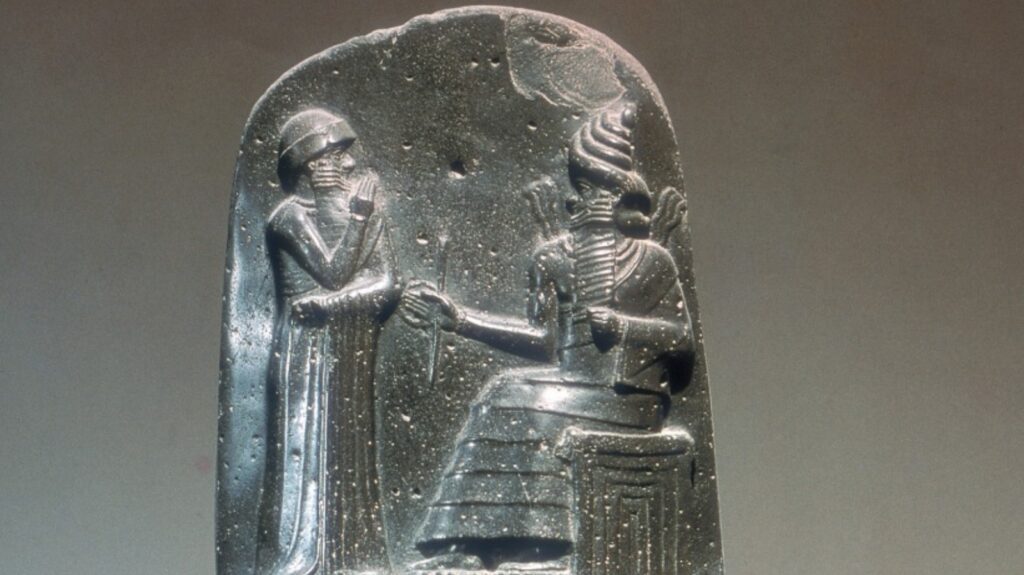

Yet, Hammurabi’s true legacy lies not just in military might, but in his groundbreaking legal code – the Code of Hammurabi. Imagine a world where laws were shrouded in secrecy, known only to a select few, open to interpretation and abuse. The Code of Hammurabi, carved onto a massive diorite stele, was a revolution.

This code, discovered in 1901, offers a fascinating window into the legal and social structures of ancient Babylon:

- 282 Laws: Covering family law, inheritance, property rights, trade regulations, and even personal injury, the code touched upon nearly every aspect of Babylonian life.

- “An Eye for an Eye”: The code is often associated with this principle of retributive justice, where the punishment mirrored the crime. However, this principle was applied differently depending on social status.

- Protection of the Vulnerable: The code also contained provisions to protect women, children, and even slaves from abuse and exploitation, a progressive stance for its time.

The Code of Hammurabi, displayed prominently throughout his empire, served several key purposes:

- Unification: It created a standardized legal system across a vast and diverse empire, reinforcing Hammurabi’s authority and promoting a sense of unity.

- Justice and Order: By codifying laws and making them public, the code aimed to establish a sense of fairness and predictability in the legal system.

- A Model for Future Civilizations: The Code of Hammurabi influenced later legal codes in the ancient Near East and is considered a cornerstone in the development of law and governance.

Despite Hammurabi’s successes, the vast empire he forged proved difficult to maintain. Following his death, internal strife and external pressures led to the gradual decline of the First Babylonian Dynasty. In 1595 BC, the Hittites, a powerful kingdom from Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), sacked Babylon, bringing an end to the First Babylonian Dynasty.

Between Empires: Babylon Endures

The fall of the First Dynasty marked a turbulent period for Babylon. The city changed hands multiple times, falling under the control of the Kassites from the Zagros Mountains. The Kassites, adopting Babylonian culture, ruled for nearly 400 years. This period, while less documented than others, saw the continued importance of Babylon as a cultural and religious center.

However, a new power was rising in the north – the Assyrians. By the 9th century BC, the Assyrian Empire, known for its military might and often brutal rule, had become the dominant force in Mesopotamia. Babylon, unable to resist the Assyrian war machine, fell under their control.

Babylon’s relationship with Assyria was complex and often fraught with tension. The Assyrians recognized Babylon’s cultural and economic significance, but they also viewed the Babylonians with suspicion, wary of their rebellious tendencies. Rebellions did occur, with one notable uprising led by Shamash-shum-ukin, Nebuchadnezzar II’s own brother, in the 7th century BC.

This constant struggle for dominance between the Assyrians and Babylonians would eventually culminate in the complete collapse of the Assyrian Empire and the birth of a new era for Babylon – the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

The Neo-Babylonian Empire: A Renaissance of Power and Splendor

By the 7th century BC, the once-mighty Assyrian Empire showed cracks in its foundations. Years of warfare, internal strife, and brutal subjugation of conquered peoples had sown the seeds of its demise.

In 626 BC, a Babylonian chieftain named Nabopolassar seized the opportunity, leading a revolt against Assyrian rule. Nabopolassar, a shrewd strategist, forged an alliance with the Medes, another powerful kingdom eager to see the Assyrian empire crumble. The alliance proved decisive. In 612 BC, Nineveh, the Assyrian capital, fell in a brutal siege, effectively ending centuries of Assyrian dominance.

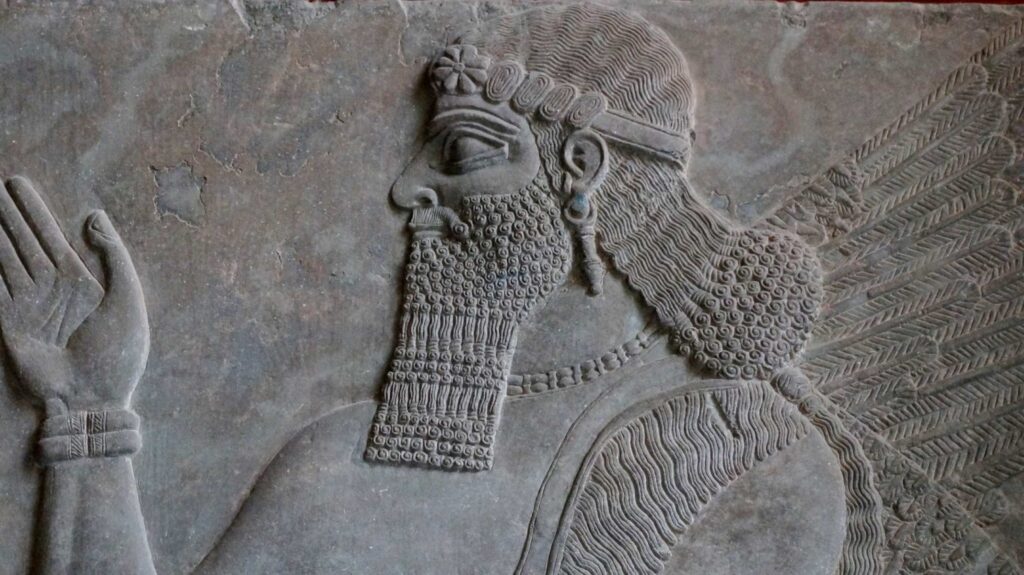

Nabopolassar’s son and successor, Nebuchadnezzar II, inherited a kingdom on the rise, and he would prove to be its most legendary ruler. Nebuchadnezzar II’s reign (605-562 BC) was a golden age for Babylon. A brilliant military strategist and a visionary builder, he expanded the empire’s reach, solidified its control over lucrative trade routes, and transformed Babylon into a metropolis of unparalleled splendor.

A City Reborn: Nebuchadnezzar II’s Architectural Legacy

Imagine a city of such magnificence that its reputation echoed across the ancient world. This was Babylon under Nebuchadnezzar II. His ambition was etched onto the very landscape of the city:

- Impregnable Walls: Babylon’s walls, considered amongst the most formidable in the ancient world, were a testament to both engineering prowess and Nebuchadnezzar II’s obsession with security. According to the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, the walls were so thick that chariots could pass each other on top! They stretched for miles, fortified by massive towers and featuring eight monumental gates, each dedicated to a Babylonian deity.

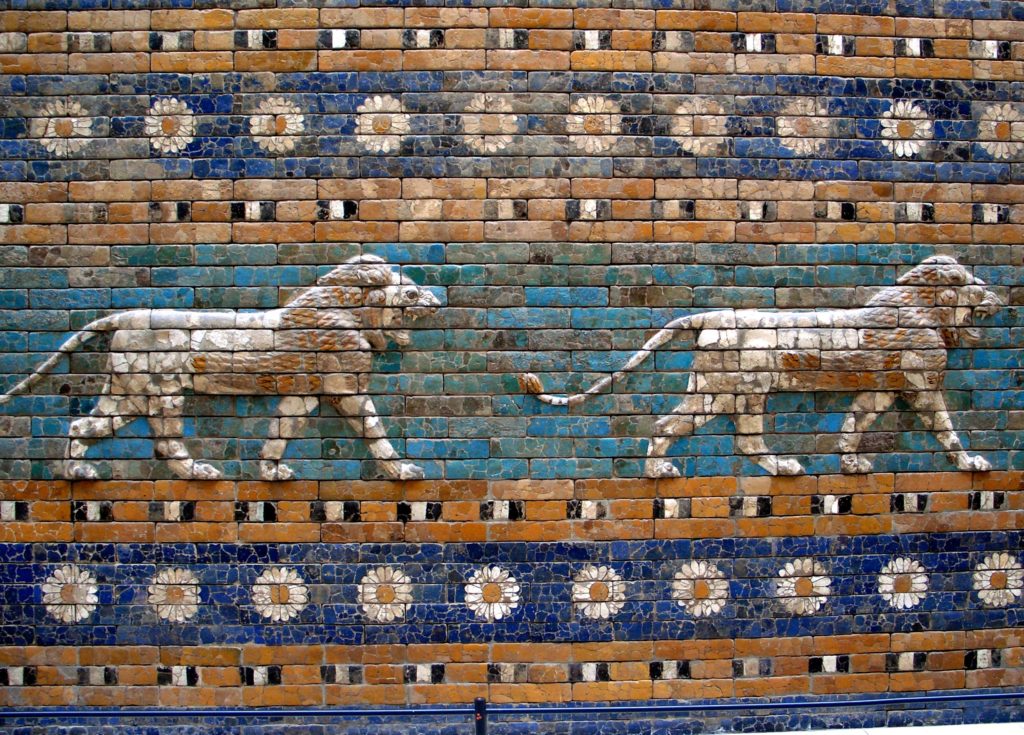

- The Ishtar Gate: Imagine a towering gateway, its facade adorned with vibrant blue glazed bricks, intricately molded with reliefs depicting majestic lions, ferocious dragons, powerful aurochs (wild oxen), and mythical mušḫuššu (serpent-like dragons). This was the Ishtar Gate, named after the Babylonian goddess of love, war, and fertility. It served as a symbol of Babylonian power and a testament to their artistic mastery.

- The Processional Way: This grand avenue, paved with limestone slabs and lined with walls adorned with glazed brick reliefs, cut through the heart of the city. It led from the Ishtar Gate to the sacred precinct dedicated to Marduk, the patron deity of Babylon, where massive religious festivals took place.

- The Hanging Gardens: Perhaps the most legendary of Babylon’s wonders, the Hanging Gardens are described by ancient writers as a botanical paradise – a series of tiered gardens, filled with lush vegetation, cascading waterfalls, and exotic plants from across the empire. Though their exact location remains a subject of debate among archaeologists, their existence, whether literal or literary, cemented Babylon’s image as a city of unparalleled beauty and innovation.

But Nebuchadnezzar II’s vision extended beyond mere spectacle. He understood the importance of infrastructure and undertook ambitious projects:

- Irrigation Canals: Nebuchadnezzar II’s engineers constructed a complex network of canals, diverting water from the Euphrates River to irrigate fields, ensuring agricultural abundance and supporting a growing population.

- Palaces and Temples: The city boasted opulent palaces, administrative buildings, and magnificent temples dedicated to the Babylonian pantheon of gods.

These architectural marvels served not just as displays of wealth and power but also as symbols of Babylonian identity, religious devotion, and the ingenuity of its people.

A Golden Age of Culture and Knowledge

Beyond its architectural splendor, Nebuchadnezzar II’s reign saw a flourishing of Babylonian culture and intellectual pursuits.

- Astronomy and Mathematics: Building upon the foundations laid by the Sumerians, Babylonian astronomers made significant strides in mapping the stars, predicting eclipses, and developing a sophisticated lunar calendar. Their mathematical advancements, including the development of a base-60 system and early forms of algebra, had a profound influence on later civilizations.

- Literature and Mythology: Babylonian scribes, working in scriptoriums, preserved and expanded upon a rich literary tradition. The Babylonian creation myth, the Enûma Eliš, became a cornerstone of their religious beliefs. This epic poem, recounting the god Marduk’s victory over chaos and creation of the world, served to legitimize the rule of Babylonian kings, linking them to a divine order.

- Trade and Diplomacy: Babylon’s central location in Mesopotamia made it a crossroads of trade, attracting merchants and goods from as far as Egypt, India, and Anatolia. Nebuchadnezzar II’s reign saw a flourishing of trade, further enriching the city and spreading its cultural influence.

However, even golden ages eventually come to an end. Following Nebuchadnezzar II’s death in 562 BC, Babylon entered a period of instability. A succession of weak rulers, internal strife, and growing economic problems weakened the empire from within, making it vulnerable to the ambitions of a new power rising in the east – the Persians.

The Fall of Babylon and a Legacy Etched in Time

The Persian Empire, under the leadership of Cyrus the Great, was rapidly expanding in the 6th century BC. Cyrus, a brilliant strategist and a shrewd diplomat, had already conquered Media, Lydia, and other kingdoms, setting his sights on the wealthy and strategically important lands of Mesopotamia.

In 539 BC, the seemingly invincible city of Babylon fell to Cyrus’s forces. The exact circumstances of the city’s fall are shrouded in some mystery, with different historical accounts providing varying details.

- Herodotus’ Account: The Greek historian Herodotus describes how the Persians diverted the Euphrates River, which flowed through Babylon, allowing their troops to enter the city through the riverbed, bypassing its massive defenses.

- Babylonian Chronicles: These cuneiform inscriptions, discovered by archaeologists, suggest that Babylon may have fallen with relatively little resistance, perhaps due to internal divisions or the belief that Cyrus would be a more benevolent ruler than their own.

Cyrus’s conquest marked the end of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. However, Babylon itself was not destroyed. Cyrus, known for his relatively tolerant policies towards conquered peoples, allowed the city to continue functioning as a regional center, albeit under Persian rule.

In a testament to Babylon’s enduring prestige, Cyrus adopted the title “King of Babylon, King of the Lands,” recognizing the symbolic importance of the city within his vast empire.

Babylon Under Persian, Greek, and Parthian Rule

The Persian Empire, under Cyrus and his successors, the Achaemenid kings, brought a period of relative peace and stability to Babylon. The Persians, recognizing the city’s economic and strategic importance, maintained its infrastructure and allowed for a degree of local autonomy.

However, Babylonian resentment towards Persian rule simmered beneath the surface. In 482 BC, during the reign of Darius I, a major revolt erupted in Babylon, challenging Persian authority. Darius, determined to crush the rebellion, besieged the city, eventually retaking it and imposing harsh punishments.

Despite this setback, Babylon remained an important city within the Persian Empire. However, its political and military significance waned as the empire itself faced internal and external challenges.

In 331 BC, Alexander the Great, leading his Macedonian army, conquered the Persian Empire, and Babylon, with barely a fight, welcomed him as a liberator. Alexander, recognizing the city’s historical importance and strategic location, envisioned making it the capital of his vast empire. He ordered the restoration of its temples and planned ambitious construction projects. However, his untimely death in Babylon in 323 BC, at the age of 32, prevented him from realizing his vision.

Following Alexander’s death, his generals fought for control of his vast empire. Babylon, caught in the crossfire, passed through the hands of several Hellenistic kingdoms, including the Seleucid Empire. Under the Seleucids, the city’s fortunes declined as the empire’s focus shifted westward, with new cities like Seleucia on the Tigris overshadowing Babylon.

In the 2nd century BC, the Parthians, a nomadic people from Central Asia, conquered Mesopotamia, ending Seleucid rule. Babylon, under Parthian control, experienced a brief resurgence as a cultural center, but its political and economic importance continued to wane.

By the 1st century AD, the once-great city of Babylon, its population dwindled and its grand structures crumbling, was largely abandoned. The shifting political landscape, the silting up of its canals, and the rise of new cities and trade routes all contributed to its decline.

Rediscovering Babylon: Unearthing a Lost Civilization

While Babylon may have faded into obscurity, its name continued to echo through history, whispered in legends, recounted in biblical tales (the Tower of Babel story originates from Babylon’s ziggurat), and preserved in the writings of Greek and Roman historians. These accounts, while often tinged with a sense of awe and melancholy, ensured that the memory of Babylon’s grandeur would not be entirely lost to time.

In the 19th century, as European explorers and archaeologists ventured into the deserts of Mesopotamia, the ruins of Babylon, half-buried in the sands, began to capture the world’s imagination once more.

One name stands out in the annals of Babylonian archaeology: Robert Koldewey. This German archaeologist, beginning in 1899, undertook systematic excavations of Babylon that would continue for nearly two decades.

Koldewey’s meticulous work unearthed a treasure trove of artifacts and architectural remnants, revealing the scale and magnificence of the city that had once dominated Mesopotamia:

- The Ishtar Gate: Koldewey’s team carefully excavated and reconstructed portions of the magnificent Ishtar Gate, its vibrant blue glazed bricks and intricate reliefs astonishing the world.

- The Processional Way: Sections of the Processional Way, with its limestone paving and walls adorned with reliefs depicting lions and mythical creatures, were unearthed, offering a glimpse into the grandeur of Babylonian religious processions.

- Nebuchadnezzar II’s Palace: The foundations of Nebuchadnezzar II’s sprawling palace complex were uncovered, revealing the opulence and grandeur in which the Babylonian kings once lived.

These discoveries, coupled with the decipherment of cuneiform inscriptions on clay tablets found throughout the ruins, revolutionized our understanding of ancient Babylon. They provided invaluable insights into the daily lives of its people, their religious beliefs, their legal system, their economic activities, and their remarkable artistic and architectural achievements.

Babylon’s Enduring Legacy: Echoes Across Millennia

The story of Babylon is a powerful reminder of the cyclical nature of empires. It reminds us that even the most magnificent civilizations rise, flourish, and eventually fade away, leaving behind echoes of their grandeur in ruins, artifacts, and the indelible marks they etch onto the tapestry of history.

Babylon’s legacy is multifaceted and enduring:

- The Foundation of Law and Governance: The Code of Hammurabi, despite its harsh punishments by today’s standards, stands as a testament to the Babylonian quest for justice, order, and a standardized legal system. It established precedents that influenced legal codes throughout the ancient Near East and continue to be studied by legal scholars today.

- Architectural Innovation: From its massive walls and imposing gates to the legendary Hanging Gardens, Babylonian architectural achievements left an enduring mark on the ancient world. Their innovative use of materials, particularly glazed bricks, and their mastery of engineering and design inspired awe and wonder in all who beheld them.

- Advancements in Science and Mathematics: Babylonian astronomers and mathematicians made significant strides in their respective fields, laying the groundwork for future scientific discoveries. Their meticulous observations of the night sky and their development of sophisticated mathematical systems, including the base-60 system that we still use today, influenced the development of astronomy and mathematics in later civilizations.

- A Wellspring of Myth and Literature: Babylonian myths, legends, and literary works, passed down through generations and preserved on clay tablets, continue to captivate the imagination. The Epic of Gilgamesh, a tale of heroism, loss, and the search for immortality, is considered one of the earliest works of great literature. These stories offer profound insights into the Babylonian worldview, their values, and their understanding of the human condition.

Today, the ruins of Babylon, located in modern-day Iraq, stand as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. They serve as a poignant reminder of the city’s former glory, the ingenuity of its people, and the enduring power of our shared human history. Though much of Babylon remains buried beneath the sands of time, archaeological excavations continue to unearth new discoveries, further enriching our understanding of this captivating civilization.

As we stand amidst the remnants of this once-great city, we are reminded of the impermanence of empires, the cyclical nature of history, and the enduring power of human creativity and resilience. Babylon’s story, though its final chapter was written long ago, continues to resonate across millennia, reminding us of the interconnectedness of our shared human journey.

Source and references:

- Oppenheim, A. Leo. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization. University of Chicago Press, 1977.

- Kriwaczek, Paul. Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. Atlantic Monthly Press, 2010.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. Hammurabi of Babylon. Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

- Wiseman, Donald J. Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon. Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Oates, Joan. Babylon. Thames & Hudson, 1986.

- British Museum. www.britishmuseum.org

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. www.metmuseum.org