The Trevi Fountain in Rome, Italy, is a place of dreams. Tourists from all corners of the globe flock to its glimmering waters, each toss of a coin a whispered wish for love, luck, or a return to the Eternal City. It’s a tradition steeped in hope, and it makes for quite a spectacle. Imagine: over 10 million visitors a year, each tossing in a coin, maybe two, maybe three! That’s a lot of wishes… and a whole lot of money. In fact, the Trevi Fountain collects around $3,800 in coins every single day.

You might wonder, with all that money swirling around, why doesn’t someone jump in and grab it? Well, someone did. Meet Roberto Cercelletta, better known in the streets of Rome as “D’Artagnan, the Thief of Coins.”

Roberto wasn’t a mastermind criminal; he was a homeless man driven by need. He started by simply scooping up handfuls of coins at night. But as time went on, and he went undetected, his methods became more sophisticated.

This was back in the days of the Italian Lira, and Roberto, in a stroke of ingenious simplicity, started using a large magnet to collect his nightly haul. This wasn’t just about speed; it was strategic. The Italian Lira coins were magnetic, while most foreign currency wasn’t. Roberto wasn’t just taking coins; he was selectively targeting the most profitable ones. His nightly hauls often reached $1,000, and he carried on this way for years, becoming a phantom of the Trevi Fountain.

The police knew about Roberto; they tried to catch him, but he was a master of timing, operating on nights when they were stretched thin elsewhere. And here’s the kicker: back then, no law existed against taking coins from the fountain. Roberto was exploiting a loophole in the system.

The authorities eventually caught up, outlawing the practice and officially branding Roberto a thief. He was arrested multiple times but always seemed to slip through the cracks, returning to his unusual trade.

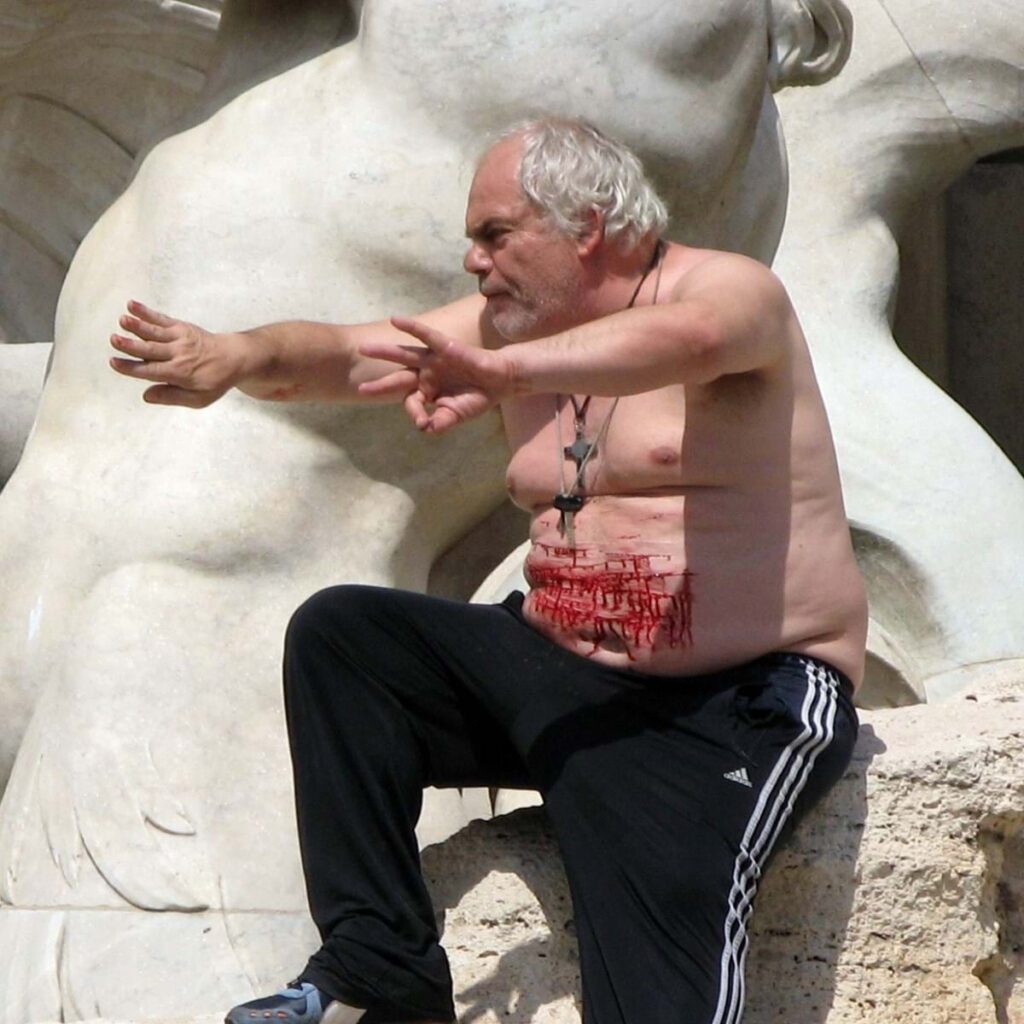

But Roberto saw himself not as a criminal, but as a citizen reclaiming what he believed belonged to the people of Rome. The fountain, a public space, was his to profit from, in his eyes. He even staged a one-man protest, declaring coin collecting his official profession. This act, covered by news outlets, thrust him into the spotlight, dividing public opinion. Some condemned him, others were amused by his audacity, and some even found themselves inspired by his defiance.

However, there was a deeper layer to Roberto’s story, one that came to light during a particularly tense standoff with the police. In a desperate act, Roberto, in full view of the cameras and tourists, began to cut himself. While bleeding, he cried out, claiming he shared the money with other homeless individuals in need.

This shocking display revealed a man grappling with mental health issues, failed by the very system he was challenging. It forced Rome to confront the plight of its homeless population, eventually leading to a decision that would forever change the Trevi Fountain.

From that point on, all the money fished from the fountain would go to charity, directly benefiting those in need. It was a victory, albeit a tragic one, for Roberto and those like him.

Roberto continued his coin-collecting ways for two decades, becoming a local legend, a symbol of Rome’s contradictions. When he died in 2013, his story found its way to the New York Times, cementing his place in the city’s lore.

So, was Roberto Cercelletta a thief or a folk hero? A nuisance or a catalyst for change? In the grand tapestry of Rome, he remains a complex figure, a reminder that even in the most beautiful of places, shadows lurk, and even the simplest act can ripple outward, leaving an indelible mark.