As a scientist, I’ve always been captivated by Albert Einstein’s story. It’s not just his groundbreaking theories that fascinate me, but the incredible path he took to reach such heights. It’s a story filled with setbacks, personal struggles, and an unyielding passion for unraveling the mysteries of the universe. It challenges the very idea of what it means to be a genius. You see, Einstein’s journey wasn’t a straightforward climb to success. It was a path riddled with obstacles, a testament to his resilience and unwavering belief in his own potential.

A Late Bloomer Who Questioned Everything

Believe it or not, Einstein wasn’t the picture-perfect child prodigy you might imagine. His parents were even worried because he was slow to start talking. Little did they know, this delayed development, as Einstein himself later reflected, might have been a blessing in disguise. It allowed him to approach complex concepts like space and time with a fresh, untainted perspective.

School, with its rigid structure and emphasis on rote memorization, felt stifling to young Einstein. He saw through the monotony, viewing his teachers as nothing more than “lieutenants in the Prussian army.” This frustration led him to make an audacious decision at 16 – he dropped out of high school, aiming to enter a teaching college in Zurich instead. This move not only allowed him to escape the dreaded compulsory military service, but also exposed the flaws in his self-directed learning. His plan backfired when he failed the college entrance exam, stumbling not on the science and math portions, but on subjects like French and history.

Forced to re-evaluate, Einstein spent a year at a Swiss high school in Aarau. Here, he thrived in an environment that valued visual learning, a method that would later become a cornerstone of his thought experiments. He excelled, gaining entry into Zurich Polytechnic to study math and physics.

University Days: A Mix of Promise and Rebellion

Even at university, Einstein’s path wasn’t paved with perfect grades. While he consistently excelled in physics, earning top marks, his performance in math was more erratic. His independent spirit, while admirable, sometimes clashed with the rigid structure of academia.

Take his physics practical course, for example. Professor Jean Pernet awarded him the lowest possible grade, not for a lack of understanding, but for his audacity in tossing aside Pernet’s instructions, preferring to experiment his own way. This independent streak, coupled with his vocal criticism of outdated teaching methods, put him at odds with some professors, particularly Heinrich Weber. When it came time to offer teaching assistant positions, Einstein found himself as the only graduate without a job offer. Weber’s resentment ran so deep that he chose engineering students over Einstein, a slight that stung deeply.

Love, Loss, and Letters of Desperation

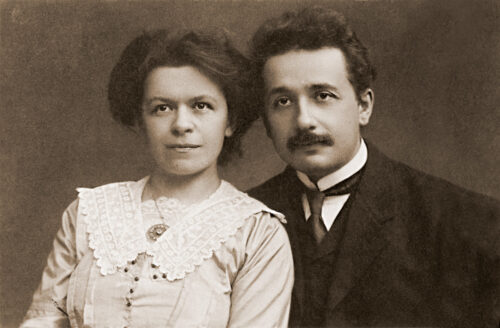

During this difficult period, Einstein found solace in his relationship with Mileva Marić, the sole woman in their physics program. Despite facing societal prejudices and physical challenges, Mileva possessed a brilliant mind that resonated with Einstein’s. They supported each other intellectually, with Mileva even reviewing his work, including his early explorations of relativity.

However, their relationship faced fierce opposition from Einstein’s family, adding to the mounting pressure of finding a job, especially after Mileva became pregnant. They kept the pregnancy and the birth of their daughter, Lieserl, a secret from Einstein’s family. The fate of Lieserl remains a mystery; she seems to vanish from historical records, likely given up for adoption.

Desperate for a stable income to support himself and Mileva, Einstein wrote countless letters to professors across Europe, pleading for even the humblest of positions. His father, heartbroken by his son’s struggles, even penned a heartfelt plea to the renowned chemist Wilhelm Ostwald, highlighting Einstein’s talent and desperation. Tragically, despite these pleas, no offers came. Anti-Semitism likely played a role, along with whispers of Einstein’s rebellious nature during his university days.

Finding Refuge (and Revolutionary Ideas) in a Patent Office

With his academic dreams on hold, Einstein settled for a position at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern. What seemed like a setback proved to be a blessing. The job, while far from glamorous, provided something crucial – financial stability and ample time to think.

Einstein found himself engrossed in the world of patents, meticulously analyzing inventions and dissecting their inner workings. This process of scrutinizing ideas, questioning assumptions, and visualizing possibilities mirrored his approach to scientific inquiry. It was in this “worldly cloister,” as he called it, that Einstein experienced his “miracle year” of 1905.

1905: A Year of Scientific Earthquakes

Imagine a single year where one scientist publishes not one, but four groundbreaking papers that reshape our understanding of the universe. That was Einstein’s 1905. Here’s a glimpse:

- The Photoelectric Effect: Challenged the prevailing view of light as a wave, suggesting instead that it also behaves as discrete packets of energy called photons. This insight earned him the Nobel Prize in 1921.

- Brownian Motion: Offered a compelling explanation for the seemingly random movement of particles suspended in a fluid, providing further evidence for the existence of atoms.

- Special Relativity: Introduced the mind-bending concepts of time dilation and length contraction, showing that time and space are not absolute but relative to an observer’s motion.

- E=mc²: This deceptively simple equation revealed the profound connection between energy and mass, forever changing the landscape of physics and laying the groundwork for nuclear energy.

These papers weren’t just incremental advancements; they were seismic shifts in scientific thought, overturning established paradigms and propelling Einstein to the forefront of 20th-century physics.

Also read: The Hungarian Genius Factories: Why So Many Great Scientists Came From Hungary

The Path to Recognition (and Personal Turmoil)

Despite his remarkable achievements in 1905, academic recognition remained elusive for several more years. Einstein continued working at the patent office, his scientific pursuits confined to evenings and weekends. He found solace in playing the violin, believing that music, particularly Mozart, reflected the inherent elegance of the universe.

His personal life, however, grew increasingly complex. The strain of his delayed academic success, coupled with the demands of family life, took a toll on his marriage to Mileva. He grew distant, his focus consumed by his scientific pursuits.

In 1909, a glimmer of hope emerged when he was offered a junior teaching position at the University of Bern. This marked the beginning of a slow but steady ascent in academia, taking him to Zurich, Prague, and finally, Berlin – the epicenter of theoretical physics. It was in Berlin that Einstein embarked on his quest to develop a theory of gravity that could encompass the insights of his special relativity – a quest that would culminate in his masterpiece, the theory of general relativity.

The Happiest Thought: Unlocking the Secrets of Gravity

Einstein’s journey to general relativity began with a simple yet profound thought experiment. He imagined a man falling freely, realizing that such a person wouldn’t feel their own weight. This led him to consider a person inside an elevator. If the elevator were to accelerate downwards at the same rate as gravity, the person inside would experience weightlessness, unable to distinguish between the effects of acceleration and gravity. This realization, which he later dubbed his “happiest thought,” formed the basis of the equivalence principle, a cornerstone of general relativity.

Einstein proposed that gravity is not simply a force, as Newton described it, but rather a curvature in the fabric of spacetime caused by the presence of mass and energy. Imagine a bowling ball placed on a trampoline; it creates a dip, distorting the trampoline’s surface. Similarly, massive objects like stars and planets warp the fabric of spacetime around them.

General relativity predicted that this warping of spacetime would affect the path of light, causing it to bend around massive objects. This prediction was spectacularly confirmed during the 1919 solar eclipse, when astronomers observed the apparent shift in the position of stars near the sun, exactly as Einstein’s theory had predicted.

From Obscurity to Icon: A Legacy of Genius and Humanity

The confirmation of general relativity catapulted Einstein to international fame. His name became synonymous with genius, his image, with his unruly hair and piercing gaze, instantly recognizable around the world. But Einstein was more than just a brilliant mind; he was a complex figure who grappled with social and political issues, often challenging societal norms and advocating for peace and justice.

He spoke out against racism, militarism, and nationalism, even as he wrestled with his own internal conflicts and prejudices. His life and work serve as a powerful reminder that genius is not defined solely by intellectual prowess, but also by courage, compassion, and a relentless pursuit of truth.

Einstein’s story is a beacon for anyone who has ever felt like an outsider, for anyone who has dared to question the status quo, for anyone who has ever looked up at the night sky and felt the vastness of the universe beckoning them to explore its mysteries.

Sources:

- “Einstein: His Life and Universe” by Walter Isaacson

- “Subtle is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein” by Abraham Pais

- “Einstein: A Biography” by Jürgen Neffe