Picture this: a city that moves. Not just a bustling metropolis with efficient transportation, but a city that traverses the landscape on colossal, mechanical legs, like something straight out of science fiction. This captivating image, etched in our minds by movies like “Mortal Engines,” has its roots not in a dystopian future, but in the hopeful, revolutionary ideas of the 1960s.

In post-war Britain, amidst a crippling housing shortage and a thirst for innovation, a group of architects known as Archigram dared to imagine a world where cities were no longer tethered to a single location. Their concept, the “Walking City,” wasn’t about conquest or dominance; it was a utopian vision of interconnectedness, adaptability, and pushing the boundaries of architecture and urban planning.

Beyond Bricks and Mortar: Rethinking the City

Archigram’s vision challenged the very notion of what a city could be. Instead of static concrete jungles, they envisioned dynamic, mobile structures that could roam freely across diverse terrains, even navigating water. This radical concept was a direct response to the limitations of traditional cities, offering a fresh perspective on urban living in a rapidly changing world.

The idea resonated deeply with a society hungry for progress and a brighter future. The post-war era was a time of immense technological advancement, and Archigram cleverly tapped into this zeitgeist, seamlessly weaving futuristic technology into their architectural concepts. Their “Walking City” wasn’t just an architectural marvel; it represented a social and cultural shift, a move away from the rigid structures of the past toward a more flexible and interconnected future.

Deconstructing the Dream: How Would a Walking City Function?

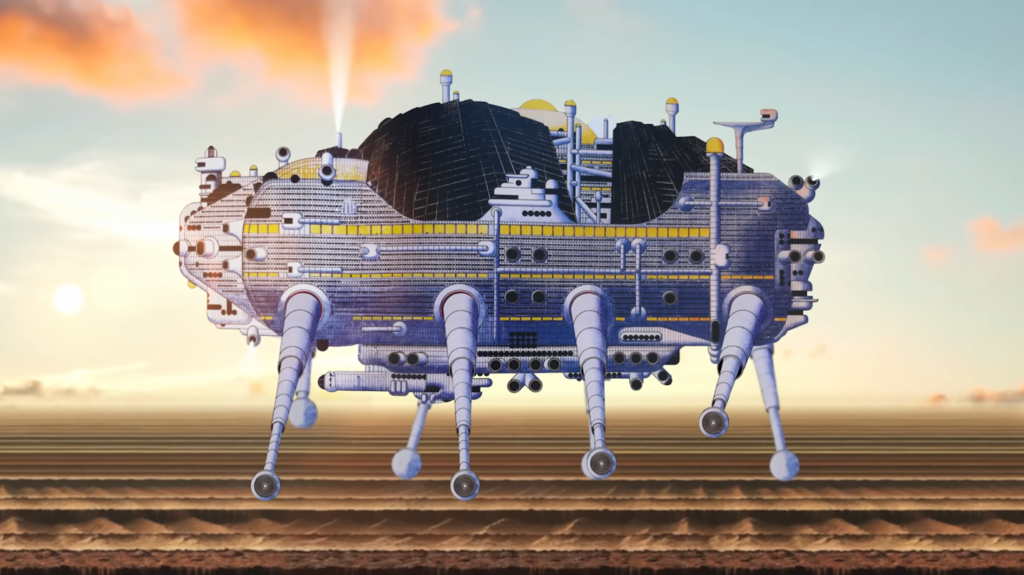

Archigram didn’t stop at fantastical imagery; they delved into the logistics of how such a city could function. Their vision was rooted in three core components, each with its unique challenges and opportunities:

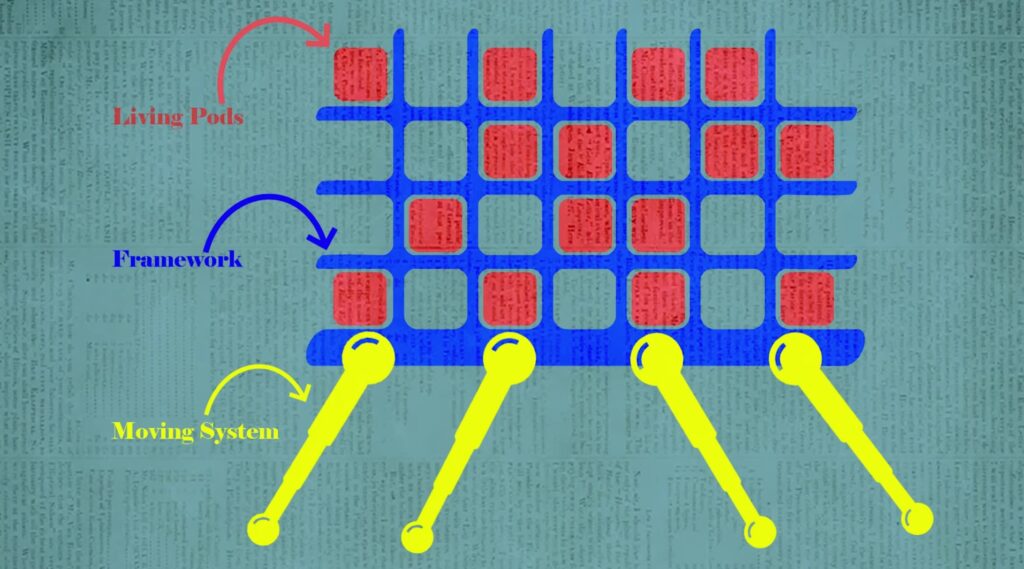

1. The Moving System: Legs, Crawlers, or Something Else Entirely?

The most striking and arguably the most challenging aspect of a walking city was its movement mechanism. Inspired by the incredible mobility of insects and the raw power of industrial machinery, Archigram envisioned massive, articulated legs that would carry the city across varying terrains. This ambitious concept, while visually arresting, presented significant engineering hurdles.

The sheer scale of these mechanical legs would require immense strength and stability, demanding new materials and construction techniques. Additionally, ensuring smooth, coordinated movement across uneven terrain would necessitate sophisticated control systems and a deep understanding of weight distribution and balance.

While the robotic legs captured the imagination, alternative locomotion systems were also explored. Massive crawler transporters, similar to those used for moving space shuttles, offered a more grounded approach. Another option involved a dual-layer railway system, echoing China’s experimental “Transit Elevated Bus.”

Each system came with its own set of infrastructure requirements and limitations. Crawler transporters, while potentially more feasible, would necessitate significant alterations to existing infrastructure, potentially disrupting existing urban landscapes. The railway system, on the other hand, would be better suited for cities with linear layouts, like Saudi Arabia’s ambitious “The Line” project in Neom.

The choice of locomotion would ultimately dictate how the walking city interacts with its environment and existing urban centers, highlighting the complex interplay between technological innovation and urban planning.

2. The Structural Framework: The “Plug-In City” Concept

Beyond movement, Archigram recognized the need for a flexible and adaptable urban structure. Their answer was the “Plug-In City,” a massive framework designed to accommodate prefabricated, modular living spaces. These modules could be easily “plugged in” or removed, allowing the city to adapt to the changing needs of its inhabitants.

This concept mirrored the principles of Metabolism, an architectural movement that gained traction in Japan around the same time. Metabolism, as its name suggests, embraced the idea of buildings as living organisms, constantly evolving and adapting. The Nakagin Capsule Tower, a striking example of Metabolism, featured interchangeable living units designed for easy replacement and customization.

However, the Nakagin Capsule Tower also exposed the challenges of modular construction. Issues with ventilation, insulation, and exorbitant maintenance costs plagued the building, ultimately leading to its demolition in 2022. The high cost and logistical complexities of replacing the modules proved insurmountable for residents.

Learning from these challenges, Archigram’s “Plug-In City” adopted a more nuanced approach. Their “Capsule Homes” were designed to be not just modular but also easily repairable. They were composed of smaller, interchangeable components, allowing residents to replace or upgrade individual parts instead of entire units, making maintenance more manageable and cost-effective.

3. The Living Pods: Living Pods Designed for Adaptability

Archigram’s living pods went beyond mere dwellings; they were conceived as self-contained units that could function independently. Equipped with self-leveling legs, these pods could adapt to various environments, further blurring the line between architecture and technology. This adaptability expanded the possibilities for the walking city, allowing it to traverse not only different geographical terrains but also different social and cultural landscapes.

The integration of the appliance mechanism directly into the core structural framework of the “Plug-In City” streamlined the process of adding or removing modules. This thoughtful design minimized disruption and additional costs, addressing a key challenge faced by the Nakagin Capsule Tower.

Reflecting Cultures: A Tale of Two Movements

The parallels between Archigram’s Plug-In City and Metabolism, despite evolving independently in different corners of the world, reveal a shared desire for adaptable and responsive architecture. However, they also highlight intriguing cultural differences in their approach to design and community.

Plug-In City, true to its Western roots, championed individual freedom and customization. Residents had the agency to personalize their living spaces, choosing modules that best suited their needs and preferences. This individualistic approach reflected a society that valued personal expression and autonomy.

On the other hand, Metabolism, rooted in Japanese culture, leaned towards a more collective approach. The emphasis was on efficiency and order, often using identical, prefabricated modules to create a sense of visual harmony and standardized living conditions. This reflected a collectivist society where the needs of the many often took precedence over individual preferences.

Neither approach was inherently superior; they represented different cultural values and design philosophies. However, by analyzing their strengths and weaknesses, particularly in the context of the Nakagin Capsule Tower’s challenges, a more holistic approach to designing adaptable and self-contained living spaces emerged.

This blending of individual expression and collective efficiency could be the key to unlocking the full potential of modular living, pushing it beyond mere architectural innovation to a cultural shift in how we perceive and design our living spaces.

A Nomadic Impulse: Echoes of the Past in a Futuristic Vision

The idea of mobile living isn’t new. For centuries, nomadic cultures around the world have thrived in portable dwellings, adapting to diverse environments and lifestyles. The Mongolian Ger, a circular, felt-covered dwelling used by nomadic herders, stands as a testament to the practicality and resilience of mobile architecture.

These Gers, constructed from lightweight, collapsible wooden frames, can be swiftly assembled and disassembled, allowing nomadic families to move with their herds across vast steppes. The efficiency of their design, honed over generations, allows for a comfortable and adaptable living space that can be erected and dismantled in a matter of hours.

However, with increasing urbanization and the allure of modern amenities, nomadic cultures are facing unprecedented challenges. Cities offer stability, access to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities that are often lacking in a nomadic lifestyle. As a result, traditional forms of nomadism are dwindling, and the knowledge and skills associated with building and living in mobile structures are at risk of being lost.

In this context, the concept of walking cities takes on a new significance. It’s not just about futuristic technology; it’s about reimagining the possibilities of mobile living in a rapidly urbanizing world. Could walking cities provide a way to bridge the gap between nomadic traditions and the conveniences of modern life?

Why a Walking City? Exploring the Motivations for Mobile Living

In a world grappling with climate change, resource scarcity, and political instability, the concept of a walking city takes on a new urgency. Imagine a city that could migrate away from rising sea levels, relocate to access essential resources, or even serve as a mobile embassy, fostering diplomacy and cultural exchange.

The potential benefits are numerous, but they come with a set of complex ethical and logistical considerations. Who decides where the city goes? How do we ensure equitable access to resources and prevent these mobile havens from exacerbating existing social inequalities?

The dystopian film “Snowpiercer,” which portrays a class-divided society confined to a perpetually moving train, offers a stark warning about the potential pitfalls of mobile living. It highlights the need for careful planning and a focus on social justice when envisioning a future where cities are no longer bound to a single location.

The Human Element: Community, Identity, and the Quest for Meaning

Beyond the technological marvels and logistical challenges, the success of a walking city hinges on a fundamental human element: community. Can a sense of belonging and shared identity flourish in a constantly moving environment?

The romanticized image of the digital nomad, traveling the world with just a laptop and a thirst for adventure, often overshadows the realities of loneliness and lack of community that many experience. Humans are social creatures, hardwired to seek connection and belonging. A city, even a mobile one, must provide more than just shelter and amenities; it needs to foster a sense of community and shared purpose.

My friend Naru, who spent years living as a nomad before establishing a stationary mobile community called Mobile Village, highlights this crucial aspect. He realized that the true essence of nomadism lies not just in physical movement but in the shared pursuit of meaning, connection, and a life lived on one’s own terms.

Naru’s Mobile Village, while not on the scale of a walking city, offers a glimpse into how a mobile community can thrive. By creating a shared space with essential amenities and a strong emphasis on community building, Naru has fostered a sense of belonging and purpose for himself and the 120 individuals who call Mobile Village home. They cook together, build together, and support each other, demonstrating that a strong community can take root even in unconventional settings.

The Future of Mobility: Beyond Walking Cities to Nomadic Communities

As we stand at the precipice of a new era defined by artificial intelligence, automation, and abundant technological advancements, the concept of a walking city, while still firmly in the realm of speculation, prompts us to reconsider our relationship with our built environment.

Perhaps the true legacy of Archigram’s vision lies not in giant, walking cities but in inspiring us to explore the possibilities of smaller, more sustainable mobile communities. Imagine self-sufficient, purpose-built communities dedicated to environmental restoration, scientific research, or artistic creation, moving across the globe, contributing to the betterment of humanity while embracing a nomadic spirit.

These nomadic communities, equipped with advanced technology and fueled by a shared sense of purpose, could represent a new chapter in human evolution, one where we are no longer tethered to a single location but free to roam, explore, and connect in ways we never thought possible.

The walking city, in its purest form, is an idea that transcends bricks and mortar, challenging us to rethink what it means to be a citizen, a community, and a part of something larger than ourselves. As we move into an increasingly uncertain future, it’s these big, audacious ideas that have the power to ignite our imaginations and pave the way for a more adaptable, connected, and meaningful way of life.